Displaying a modern day fast jet requires skill, training and planning, as well as physical and mental strength. Flight Lieutenant Noel Rees, the Royal Air Force’s 2014 Typhoon Display Pilot, told Gareth Stringer what life is like in his office.

“Today, at RAF Waddington International Airshow, we’re displaying at just before 1400 hours, so two hours before that I will essentially leave the airshow behind and get in to my ‘mission bubble’.

Flight Lieutenant Noel Rees – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“We’re quite lucky here as the aircraft and the engineers are on the far side of the airfield, so that means I can leave the distractions over here while I get ready to fly.

“Prior to that I will have attended the Pilots’ Briefing, which is a very important part of the day. It gives me the weather, the planned running order and the rules and regulations for the show. I also check the NOTAMs (Notice to Airmen) to ensure there is nothing else happening in the local area that I need to know about. Then I am ready to go across and complete my planning and briefing for the trip.

It’s most definitely a team effort – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“As the display pilot I actually brief and authorise myself for the trip, although I have already briefed my supervisors back at RAF Coningsby, which I do before heading to wherever the team is based or displaying at the weekend. My supervisors know everything I am scheduled to be doing while I am away for the display, and I also call them when I have landed to debrief them, so, while they are not always with me at an airshow, they are very much in the loop.

“In many ways the display is exactly the same every time I do it, and that’s why we do so much work-up. The venues change, but the whole show doesn’t change – I’ve learned my lines, if you like, and I just need to make sure the headings are correct as runways and display lines are all orientated differently. The weather is another variable too!

Nearly time to go flying – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“Mentally, though, I concentrate entirely on the display, and I don’t factor the crowd in to that, so it really doesn’t matter whether it is an audience of 1,000 or 150,000. I can see the crowd at one or two points during the routine, but it is not something that I allow to distract me. It could be just another of those practice trips that I flew so many of earlier this year.

“That’s because displaying a jet like the Eurofighter Typhoon at low level is a big deal, and it is certainly not something we normally get to do. The first concern is always for the safety of those watching the display, and secondly it is showing the best of the aircraft off, to the best of your ability. There would be little point taking off, performing the same turn three times, and then landing again!

Noel in full flow – © Karl Drage – www.globalaviationresource.com

“So I designed something that I think shows a little bit of everything Typhoon has to offer, and there are always a lot of interested parties watching; whether it is the general public who want to see what the UK’s combat capability is, or people from industry, with the possibility of export sales, and even other pilots, too.

“Back to the cockpit then, and any nerves have usually passed by the time I am airborne and have been cleared to display, and I’ve found that the only time I really feel nervous is just before taking off. Without engineering support from the team the display wouldn’t happen and I know that when I reach the aircraft the mechanical, avionics, and computer systems will all be ready. I perform a traditional pre-flight check on both aircraft, so the spare is ready should I need it, and then take my time getting strapped in and programming the headings and radio frequencies in the cockpit. Today I am going to depart using a performance take-off, which will get me quickly clear of Waddington as the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight will be due to display. Then I will join up with the Supermarine Spitfire for the D-Day commemorative flypasts, just prior to my own solo display.

Performance take-off – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“Running in to start the show, the important thing is getting the timings right, and I actually feel that if I am doing that, and I am on the correct heading and at the right speed, then I feel very relaxed in the cockpit. It is as if the first hard part of the display is over, and I can relax in to the rest of it. As I reach datum (crowd centre) and pull in to that first manoeuvre, this is the point where I am totally in my mission bubble. I am absolutely focussed and nothing else matters other than the display.

“I do look outside, but I also use the HUD (Head Up Display) for positioning – it’s a mixture of the two. I position myself visually on the 230 metre line, and that will be affected by the wind, so I have to adjust accordingly. The HUD is used for the heights and the speeds, but I spend very little time looking down in to the cockpit, unless I need to check something in an emergency, for example. Those are extremely rare, though, and we train for them occurring during a display using the excellent Typhoon simulators at RAF Coningsby.

Pre-flight checks – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“One other important thing I do need to monitor during the display is fuel burn, so I do have one of the cockpit displays set to that page, where I can keep an eye on it, but other than that, I am looking outside or using the HUD.

“We are blessed with great kit and personal equipment for the Typhoon, but flying the display is still a very physical experience. Because of the equipment we are able to sustain +9G without really having to strain that much. The squeezing of the legs, and then squeezing of the chest and the pressure breathing to inflate the lungs all combine to squeeze the blood upwards, to where it needs to be.

Pulling G – Shaun Schofield © www.globalaviationresource.com

“We do strain against it initially, as the G comes on, mainly to check that all the kit is working, but once the G is there, you can actually relax a little. The other important thing is that I keep my mouth open, so if you were to take my mask off during the display it would probably look quite amusing – I just sit there with my mouth agape, letting the air flow in as much as possible.

“The two areas we can’t squeeze are our arms, as you have to hold on to the stick. But for some portions of the display, the throttles are simply left in full afterburner, so you might see me using the hand hold on the left-hand side of the canopy. This isn’t the Typhoon equivalent of driving your car with your window open and your arm hanging out in a super relaxed fashion, I’m actually elevating my arm above my heart, while pulling G, to stop the blood pressure in my arm increasing.

The quiet time in the cockpit, pre-display – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“The only time you really feel pain from the G is in your arms, and holding the stick is mandatory, obviously, so raising the other arm helps alleviate the pain. Despite that I do suffer from ‘G measles’ as we call it, on my right arm, where the blood capillaries burst and you get small spots on the skin, but they calm down and disappear overnight. It’s not massively uncomfortable or painful, but raising the left arm does help.

“For the majority of the display I’m at around 300 knots, so I can stay closer to the crowd, and the max-rate turn, for example, is flown at around 230 knots, to show just how tight it can be. Most of those turns at 300 knots are flown at a sustained +6G, and only once or twice do I actually go all the way up to +9G.

Taxying out – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“The biggest physiological danger can be big swings from positive G to negative G, from +9G to -3G, for example, so to mitigate against that, we have tried to spread those out as much as we can, so there is a nice gap between them in the display. The negative G is probably the most uncomfortable, as the blood rushes to the head, and even other pilots wince at those bits! Overall, I would say that flying the display is physically very intense, no doubt about it, and I think the eight minutes or so of the routine equates to a hard 20 minute session in the gym, but I do have a very cool, air-conditioned cockpit to do it from and usually the hottest parts are strapping in and then at the end when I get out, when I am at the mercy of the sun again!

“Flying the Eurofighter Typhoon is actually very easy, and that might come as a surprise to some people. The jet has what we call ‘carefree handling’, and what that means is that I don’t monitor the limits, the aircraft’s computers monitor them for me. I can pull the stick fully back and it won’t overstress the aircraft or anything like that, it will always give me the best performance that it can.

“I don’t monitor the limits, the aircraft’s computers monitor them for me.” – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“The display manoeuvres aren’t necessarily technically difficult, the key is linking everything together and while we want it to look great for the crowd, the first consideration is always safety, as I said earlier. In some ways, flying the display is an exercise in maths – headings, speeds and heights. Every time I am about to perform, I go through the display in my head about four times before I have even reached the cockpit, and about twice more when I am in the cockpit. I sit quietly with my visor down and go through everything that I need to, and by then I should know which routine the weather will let me fly – full, limited or flat. Nothing disturbs me for that six or seven minutes, and I even move my hands in to the positions they will be in when I’m actually flying it.

“I don’t really feel that I’ve enjoyed the display until the very end. I do enjoy it, and am enjoying it, but I can only really be aware of that when it is over, such is the concentration required. There just isn’t the time to think ‘this is great’ and I only get about ten seconds during the slow-speed section to even take a quick look at the crowd.

Pulling up! – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“It’s always nice to be told that it was a good show, and often I will speak to the Flying Control Committee or Flying Display Director afterwards too; they are all hugely experienced, so if there is anything they want to tell me, or feedback they want to give me, then I want to hear it.

“Display weekends can be very busy, so we limit ourselves to two displays per day. We leave a nice gap between them so we can refuel the jets and so I can refuel too. We don’t display at the same venue twice on the same day, so I have to go through my whole two-hour process again for a second display and the headings will probably be different, so there are new numbers to memorise, and the weather might have changed too. Even getting from one venue to another can be intense, especially on a lovely summer day when there is a lot of general aviation traffic. I can use the Typhoon’s radar, which is a great asset, and I can also use Typhoon’s performance to take me up to a height where I simply don’t have to worry about other air traffic during a transit.

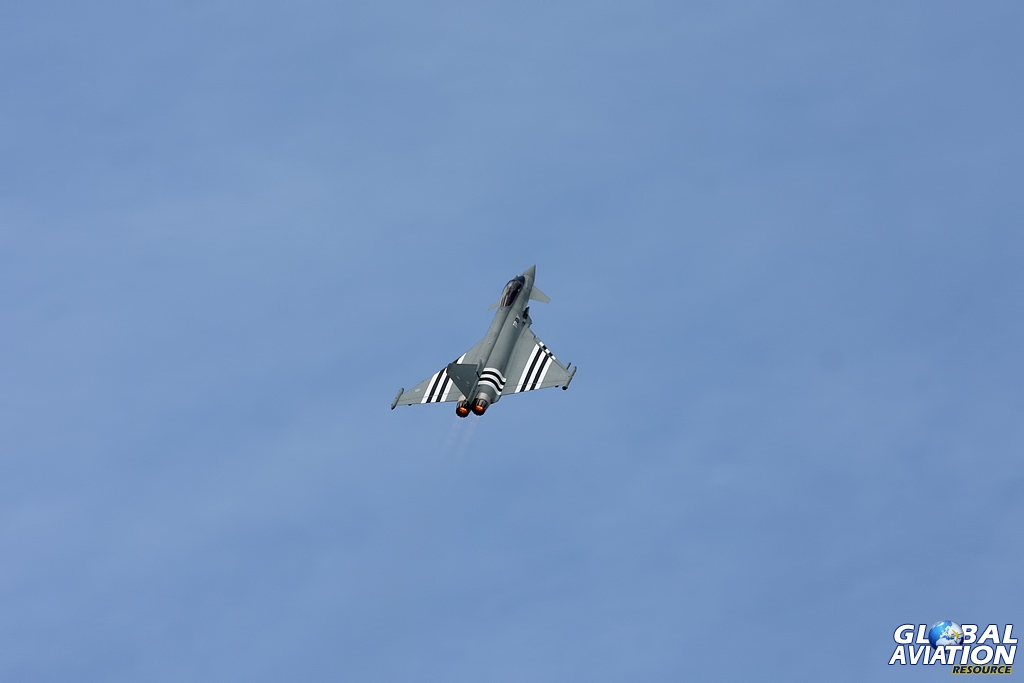

Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4 – Gareth Stringer © www.globalaviationresource.com

“This job isn’t all about flying either, although that is always my primary focus. There is a big public relations and engagement programme too, although I generally leave those arrangements to my Display Manager and the team.

“It’s great to meet the public, though, especially youngsters who might tell me that they want to join the Royal Air Force. My interest in aviation started when I was their age and in some ways I can see myself, 20-odd years ago, when I meet children of that age – and it’s superb to think that the display is inspiring them in that way.

2014 Royal Air Force Typhoon Display – Shaun Schofield © www.globalaviationresource.com

“Being the Typhoon Display Pilot is definitely the highlight of my career so far. If someone comes up to me and says ‘I want to do this, I want to fly Typhoon’ then that’s a win as far as I am concerned. You don’t have to be a super-human to fly in the Royal Air Force, you can do it, and if the display inspires people to do that, then it’s working.

“It’s hugely rewarding. Flt Lt Jamie Norris had a great season in 2013 and hopefully I have carried that on. Jamie is my mentor this year, and we went through my display together; a lot of work went in to it, and he played a big part in that. Our aim was make this year’s display better than last year’s, and my aim will be to help the 2015 display pilot make it even better still. We want this to become the best display, by the best aircraft.”

[youtube=http://youtu.be/o3Y9Hkr5k3s]

Gareth Stringer would like to thank Flt Lt Noel Rees and Flt Lt Andy De Gier. You can find the Typhoon Display Team on Facebook and Twitter.

Great Video Air Show many thanks

Great pics and love the vid! Always enjoy the Typhoon display, and have a great respect for the pilots that make airshows such a great spectacle. Unfortunately my interest in flying came to late (nearly 60 now)but did manage to fulfill my dream of flying in a fast jet last year in the rear of one of the Gnat Duo aircraft flown by Kev Whyman, which, shall we say, enhanced the respect for pilots and the “G” experience. Looking forward to seeing you at Eastbourne next month, I shall keep fingers crossed for clear weather. Best wishes for a continued successful season.

I saw the display at Waddington so it is particularly interesting to read Noel’s account of preparation and how he feels mentally and physically at different points of the routine. Lots of new information for me, which actually increases my respect and admiration for the display pilots and teams.

Lovely photography, as ever, and what a superb video! Maybe one day we can see one of the whole routine, but this one is excellent anyway.

Many thanks to all concerned.

Thank you Peter, for this and all your support. It really is appreciated! Gareth