771 Naval Air Squadron disbanded on 22 March 2016, formally marking the end of Royal Navy Search and Rescue operations in the UK. Joan le Poole and Sander Meijering visited RNAS Culdrose to speak to and fly with the squadron during its final weeks as an active unit.

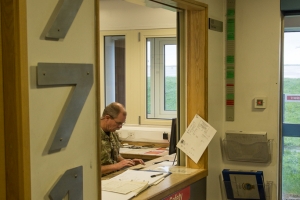

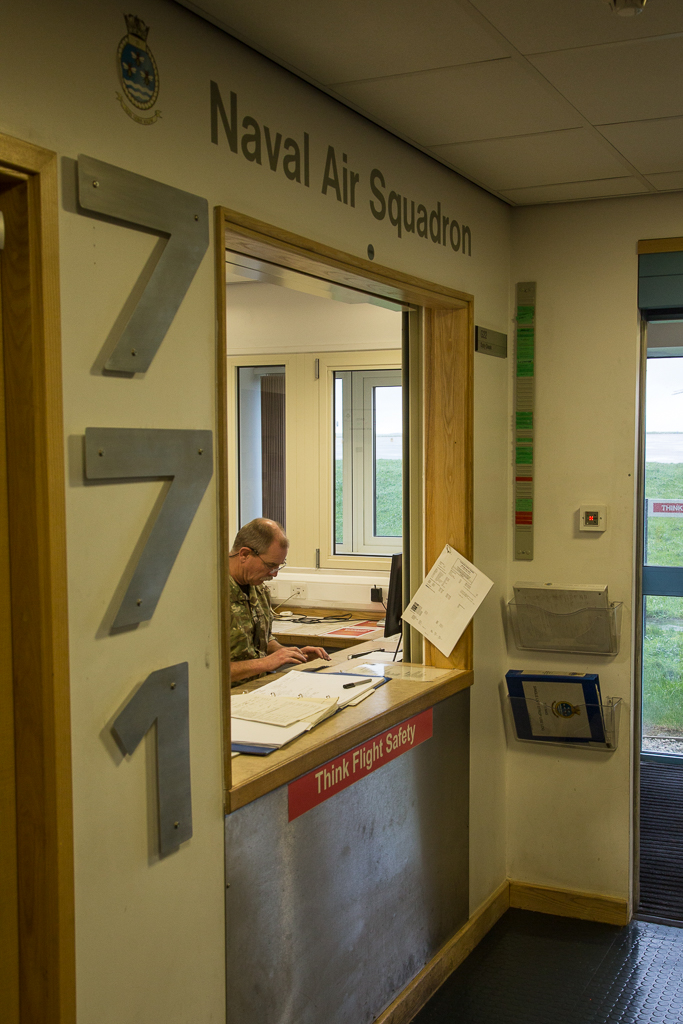

The emptiness of the operations building suggests its inhabitants are preparing to leave – it’s early February when we enter the home of 771 Naval Air Squadron (NAS) at Royal Navy Air Station Culdrose. The plaque in the hallway lists the squadron’s current members, but there are many empty spaces as we go. These are some of the many signs which show that the end for 771 is imminent and by the time you read this, the squadron will have disbanded after years of distinguished service. The recent change in Search and Rescue (SAR) operations in the United Kingdom brought an end to a long history of Royal Navy SAR operations, and 771 Naval Air Squadron was one of the last two units to fly the venerable Sea King in this role.

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

Tasks

Our host, Lt Cdr Watts, discussed the tasks 771 NAS carried out on a daily basis. The unit operated its eight Sea King Mk5s in the SAR role but also served as a training unit for Sea King crew and engineers. Following cessation of operations, this number has been reduced to three serviceable aircraft and another Sea King is due to be placed as a gate guard at RNAS Culdrose. 771 NAS is one of the last two Royal Navy units to serve in the SAR role, the other being the HMS Gannet SAR Flight based at RNAS Prestwick, Scotland.

On call 24 hours a day, every single day of the year, 771 NAS provided SAR cover over the South-West of the United Kingdom, covering Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and the Atlantic Ocean and the Channel up to 200 nautical miles from RNAS Culdrose, but could extend the range by 35 nm when refuelling at St. Mary’s Airport on the Isles of Scilly.

The majority of the missions consisted of medical rescues in Cornwall and medical transfers from the Isles of Scilly. But there was also a considerable amount of SAR at sea or from the indented coastline. On average, more than 80% of the missions were tasked by either the Coast Guard or the South Western Ambulance Service, with many of the scrambles taking place in adverse weather conditions. High wind speeds combined with high waves and difficult terrain required skill, professionalism and dedication from the aircrew, and 771 NAS’ staff are proud to have been part of the SAR community. Sea King pilot KPT LT Volkwein describes SAR as “the most satisfying job” and says, “For us it’s the normal job but the casualties are delighted when we show up.” The crews of 771 really live the squadron’s motto, “non nobis solum” which means “not unto us alone“.

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

History

Today SAR is a specialisation within the military, but that hasn’t always been the case. The roots of SAR lie in carrier aviation. In the 50s, when helicopters became widely used in the military, the Royal Navy understood their practical use during carrier operations. Due to the high incident rate during the early days of jet aviation, the Navy decided to always keep a helicopter airborne during carrier operations. This helicopter, also called the ‘plane guard’, was on standby to pick up ditched crews in the case an accident. That’s where the Royal Navy first experienced SAR operations.

On 31 January 1953, this came in handy after extensive flooding in East Anglia and The Netherlands. The Royal Navy responded to the flooding by sending twelve Dragonfly helicopters of 705 Naval Air Squadron to the rescue. These Dragonflies from RNAS Gosport rescued more than 840 people over the course of seven hours. In early 1953, the Royal Navy also decided to use their land based helicopters for SAR. This event marked the introduction of land-based SAR operations for the Royal Navy. All units with helicopters suitable for the task became involved in this, with their main task to rescue downed Fleet Air Arm pilots. After a few months there were seven bases with SAR helicopters scattered across the UK. From then, the organisation of the SAR operation slowly became more professional.

The Dragonfly was supported by the bigger Whirlwind HAR1/3 helicopter in 1954, and in 1967 the Dragonfly was completely replaced by the more capable Wessex HU5, which could rescue up to 16 people per sortie. In 1971 the Westland Sea King HAS1 was introduced into the Royal Navy to support the Wessex; this helicopter was operated in the anti-submarine warfare role and carried out the SAR calls further away due to its increased range and endurance compared to the Wessex.

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

771 and SAR operations

During its history, 771 NAS has carried out many different tasks since the unit was founded at Lee-on-Solent in 1939. During the Second World War the squadron flew a wide range of fixed-wing aircraft and in 1945 it received its first helicopter, a British license-built version of the Sikorsky R-4 called the Hoverfly, as an addition to its fixed wing aircraft fleet. This gave the squadron the distinction of being the first Royal Navy unit to operate helicopters. In 1950, the helicopters were transferred to the newly formed 705 NAS while 771 NAS continued to fly fixed-wing aircraft until its first disbandment in 1955.

In 1961 the squadron was reformed at RNAS Portland as a trial unit for the Whirlwind and Wasp helicopters, with two of the former performing SAR duties. 771 NAS continued this task till the unit was absorbed by 829 NAS in 1964. In 1967 the unit was reformed again at RNAS Portland to carry out two tasks – Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and Search and Rescue. To perform this task, 771 NAS received nine Whirlwind helicopters which were replaced by the bigger Wessex helicopter two years later. In 1973 the ASW task was passed down to 773 NAS, and SAR became the unit’s primary task.

771 moved to RNAS Culdrose in 1974, where it remained until disbandment in March 2016. All of 771 NAS’ aircraft and some of it aircrew were send to different squadrons in the South Atlantic to take part in the Falklands War of 1982. During that time, the Royal Air Force temporary took over the homeland SAR duties ordinarily carried out by the squadron until 771 took back this responsibility in August 1982. The squadron initially operated just two Wessex helicopters, with that number increasing until 771 returned to full strength in 1983. In 1988 the first Sea King helicopters were introduced – the type was already in use for ASW, and some were adapted for 771’s SAR duties in 1988. Since then the Sea King Mk5 has been the backbone of 771 and the Royal Navy SAR fleet.

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

Sea King

The Sea King is a British license-built version of the American Sikorsky S-61. The Sea King has been manufactured by Westland and differs considerably from the American version. The British helicopter uses Rolls Royce instead of General Electric engines and is fitted with a computerised flight control system. Originally the Sea King was an ASW helicopter, with the primary task of hunting Soviet submarines.

The Sea King’s flight control system makes it a very stable platform – perfect for SAR operations – and is a reliable helicopter which and can fly under almost any circumstances. Only icy conditions will stop the Sea King from flying. The Mk5 version used for SAR differs from the ASW version with extra seats and medical/rescue equipment racks replacing the anti-submarine station, and the dopping sonar removed entirely.

Lt Cdr Watts explains, “the Sea King has the same equipment on board as an ambulance. Working space is limited and poorly lit”, with “only a few dim lights in the roof.” The Sea King crew consists of four aviators: two pilots, an observer/radar operator and an aircrewman. Both the observer and the aircrewman are trained to operate the winch and they are trained as Hazardous Environment Medical Technician (HEMT) as well, which is roughly equal to a paramedic in a civil ambulance.

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

SAR Ops

With 771 NAS working towards its disbandment and SAR duties now concluded at the time of our visit, the squadron’s ops room looks empty. A normal SAR shift would start around 0800 with an extensive briefing beginning with a weather brief by a meteorological officer. Other aspects discussed during the briefing are possible diversion airfields around RNAS Culdrose, the technical state of the helicopters and the flight planning for the day. To make sure SAR missions will always have an aircraft available for flight, there are always two helicopters on call.

A regular SAR shift would last for 24 hours. This means the crew on duty sleep on base. The crew normally had 15 minutes to get airborne during daytime and 45 minutes at night after receiving a call. However, on most occasions they took off well within the time limits. Preparation is key in getting the time between the call and take-off as short as possible. The whole ops room is filled with maps and charts to be prepared for every possible scenario. In the middle of the room a large chart shows the range of the helicopter under normal circumstances both with and without refuelling on Scilly. The map on the wall shows the other areas in detail, including Cornwall and Isles of Scilly. Lt Cdr Watts explains that the strategy of the sortie itself depends on the mission profile and the location, but “the primary focus lies on which is the best for the patient.” This means that it is sometimes better to fly not to the hospital in Truro, but to an Irish hospital.

The board in the corner of the ops room shows the amount of rescue missions carried out in 2015, specified by month and type. The total hits a stunning number of 283 missions, with a total of 258 lives saved. Each of those numbers, written on the board in marker pen, carries a unique story. One of Lt Cdr Watts’ remarkable stories happened in October 2013; the Sea King crew received a call to pick up a heavily pregnant woman on the Scilly Isles. During the flight back to the hospital in Truro, the baby decided it had had enough and came into the world while flying over Cornwall!

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

The Panamera Rescue

Another pilot who has some remarkable stories is Kpt Lt Volkwein. He is a German Navy Sea King exchange pilot and the last to be in the Royal Navy/German Navy exchange programme. He has been in 771 NAS since 2011 and will return to Germany after the disbandment of the squadron. One of his most remarkable missions was the rescue of the crew of the French fishing vessel Panamera in November 2013.

The vessel got in trouble during a storm and was taking on water. The sea was rough, with a swell of four to five metres, and the wind was blowing with gale force 8. When the SAR crew received the call it was around an hour after midnight and the helicopter took off at 0130. When arriving on scene it became clear that the situation was only getting worse. The Sea King winched down a pump so the fishermen could pump out the incoming water. After some minutes of pumping it became clear the water was coming in much faster than they could get it out and the vessel was slowly sinking. The sailors decided it was time to abandon the ship and deployed their life rafts. However, due to the large waves and strong winds, the life rafts were lost before anyone could get inside.

Therefore the Sea King had to rescue them. The first two sailors were winched off the heavily listing vessel which had lost all steering and rocked up and down on the waves. Both the pilots and the crew in the back had to do their utmost not to get the winch hook stuck. The third person was lifted off the vessel as it sank. The two remaining sailors jumped in the water and were winched out by the Sea King a little later. Kpt Lt Volkwein says, “it was an eerie sight to see the glow from the light of the vessel which still shone from under water. It was exactly like you see in the film.”

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

© Joan le Poole – Naviation

The end of an era

The end of 771 NAS also marks the end of military SAR in the UK. The RAF SAR units have already disbanded and so has the HMS Gannet SAR flight, which was decommissioned on 4 February 2016. After more than 60 years of SAR, and thousands of lives saved, an era comes to an end. The future of British SAR lies in the hands of Bristow Helicopters, a civilian company.

This company, originally from Aberdeen, has more than 40 years of experience in SAR all over the globe. Bristow started in 1955 as an offshore helicopter service provider in the UK and has provided SAR since 1970. In 2013 Bristow won the UK SAR contract for the sum of £1.6 billion GBP, for which they will provide nationwide search and rescue for the next ten years. The contract replaces all air force and navy SAR operations; the current transition from military to civilian SAR is likely to be the beginning of an era of dedicated civilian SAR operations.

We would like to thank 771 Naval Air Squadron and the Royal Navy for making this article possible. We would especially thank Lt Cdr Watts and all the crew of 771 for their hospitality.